Health as an investment: time to shift the rhetoric

2 July 2025

Governments should be rethinking healthcare as a foundation for economic growth

Nearly 25 years ago, macroeconomist Jeffrey Sachs – chairman of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Commission on Macroeconomics and Health – demonstrated a linear relationship between a country’s health (measured in life expectancy) and economy (measured in GDP). This work helped coin the phrase ‘health equals wealth’: investing in health today yields a healthier and wealthier future for all, and this is true in both higher-income and lesser-resourced countries.

The centrality of health to economic growth became tragically evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic’s impact was measured not just in the number of lives lost, but in revenue lost across multiple sectors. Many of us hoped that it would act as a wake-up call to governments, demonstrating the importance of investing in population health, strengthening the resilience and sustainability of health systems, and addressing the underlying social inequalities that contribute to disparities in health.

Unfortunately, that message seems to have been eclipsed by global events, including wars and conflicts, disinvestment from international development and sluggish economic growth. Against this backdrop, there has been a shift in rhetoric, with healthcare often called out as an unsustainable cost rather than an indispensable investment. Particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), there has been a general trend towards deprioritisation of healthcare in post-pandemic recovery spending – so much so that the World Bank has suggested that the transformative period for global health envisioned in the past decade risks turning into an era of ‘limited gains and unfulfilled promises’.

In response to this shift, there have been multiple calls to reframe investments in health as a strategic investment in economic growth and social prosperity – and to demonstrate that they present an opportunity, not just a cost, that will ultimately benefit everyone in society.

There have been multiple calls to reframe investments in health as a strategic investment in economic growth and social prosperity – and to demonstrate that they present an opportunity, not just a cost, that will ultimately benefit everyone in society.

Adopting a ‘health for all policies’ mindset

Over the past few years, several health policy thought leaders have advanced the notion of ‘health for all policies’, demonstrating that carefully crafted health policies can also benefit other policy areas. This interdependence of policy objectives is embedded in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), showing that health and other priorities are not only closely interlinked, but mutually reinforcing, and all contribute to greater economic and social prosperity.

Investing in health offers a clear return on investment

This theory is illustrated in the case of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which account for 75% of deaths globally and carry a considerable economic burden in terms of healthcare costs and lost productivity. Out-of-pocket payments for health expenses related to NCDs also push an estimated 100 million people globally into extreme poverty every year. Yet despite these figures, there has been chronic under-investment in NCDs, particularly in LMICs.

To help stimulate global investment in NCDs, the WHO published its ‘Best buys’ – a list of interventions covering risk reduction, treatment and other facets of care that are deemed cost-effective and evidence-based. Implementing the ‘Best buys’ would require, on average, an additional global investment of USD $18 billion annually from 2023 to 2030, but it would ultimately save 39 million lives and yield an average net economic benefit of USD $2.7 trillion – an overall return on investment of 19:1. Thus the cost of inaction on NCDs is far greater than the investment required.

Addressing healthcare workforce shortages could eliminate 7% of the global disease burden and add USD $1.1 trillion to the global economy.

Other analyses confirm a high return on investment in health. A 2024 report by the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health suggested that by providing a limited set of interventions focused on 15 conditions, countries of all income levels could halve premature mortality by 2050, with consequential economic returns. Another report suggests investing in health – both in terms of sufficient resourcing of known interventions and investing in selected promising innovations – would yield an 8% boost to global GDP, with a return of USD $2–4 for every USD $1 invested. And addressing healthcare workforce shortages could eliminate 7% of the global disease burden and add USD $1.1 trillion to the global economy.

The social value of health interventions

Mirroring the ‘health for all policies’ approach, several authors have suggested that the evaluation of individual healthcare interventions (such as medicines or diagnostics) take a comprehensive approach, looking beyond the immediate and direct healthcare costs and benefits associated with a given technology, and including the longer-term impact in terms of reduced hospitalisations and increased productivity for both patients and carers. One approach quantifies the social impact of interventions, including not just quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) but also GDP contribution through productivity gains. The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research takes another approach, including considerations of importance to patients such as the value of hope and knowing in its proposed ‘Value Flower.’

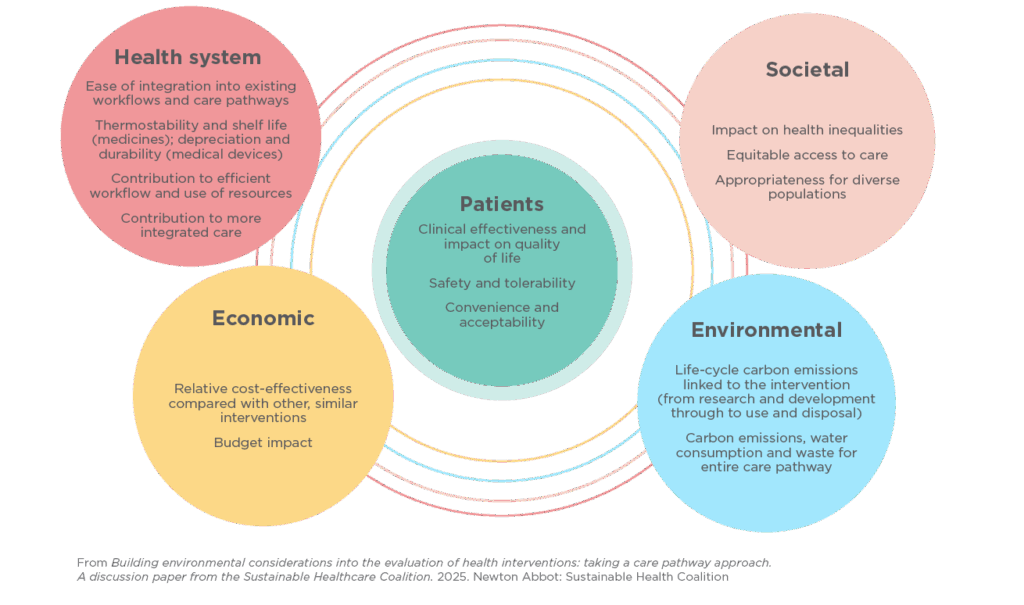

Another way to look at the comprehensive value of an intervention is to think of ‘the value for whom?’ and assess the value of an intervention based on a careful balance of costs and benefits for the patient and their family, the health system, the economy and the environment (below).

Moving from theory to practice

Implementing these concepts in practice is complex. Health technology assessment (HTA) and similar agencies have been established in many countries to guide funding decisions for medicines and other technologies based on an evaluation of their relative costs and benefits. Yet most of these agencies adopt a fairly narrow definition of ‘value’ in their appraisals, limiting their assessment to the immediate impact of an intervention on the health system. However, administering a given treatment may result in longer-term benefits such as a reduction in hospitalisations, or may enable individuals to remain active and in the workforce. Omitting these considerations from value assessments may thus result in missed opportunities to improve not just health outcomes but also the longer-term sustainability of our health systems and societal gains in productivity.

At the same time, there are growing disparities in access to medicines and diagnostics both between and within countries, making it a priority for all countries to find feasible ways to advance equitable access to value-based interventions. There are also considerable differences in the time it takes for new medicines and technologies to reach patients, and several countries have created accelerated regulatory pathways to enable patients to safely access potentially promising medicines and technologies even before complete clinical trial data are available; others have also created special innovation funds and managed entry agreements with industry.

The impact of investing in research

There is also a broader issue that, to continue to advance care and population health, investing in innovation must be a core mission of governments. This starts with ensuring continuous investment in the research that underpins advances in healthcare. Despite a 38% increase in global clinical trials over the past decade, Europe’s share has dropped from 22% in 2013 to 12% in 2023 – the equivalent of 60,000 fewer clinical trial places for European patients. This is troubling not only for patients but for wider society: aside from being a crucial avenue for people to access promising medicines and interventions, clinical trials are a source of economic growth. An analysis conducted for Cancer Research UK found that every GBP £1 invested in cancer research generated GBP £2.80 in economic benefit (2020–21 figures) – including employment, additional earnings for people with cancer and monetised patient health benefits.

Aside from being a crucial avenue for people to access promising medicines and interventions, clinical trials are a source of economic growth.

Optimising efficiency and system readiness for advances in care

While policies fostering investment in science and innovation are crucial, they alone will not necessarily translate into better health and healthcare. It’s equally important to ensure health systems optimise use of key resources – human, technical and otherwise – and integrate innovations as efficiently and effectively as possible. This requires alignment of funding streams, workforce, resources, infrastructure and patient information.

When introducing new interventions, we need to focus on how they are delivered in routine settings for their true societal value to be achieved. This means optimising care pathways to enable targeted approaches to diagnosis and treatment; engaging people in their care to encourage self-management and adherence; workforce planning to ensure the right set of skills is available across clinical teams, and professional training to enable those teams to deliver care with confidence; and optimising the use of data and technology to improve the efficiency, precision and coordination of care.

Getting it right: taking a partnership approach

Balancing these priorities is a tall order and will invariably require stakeholders to work together to find feasible solutions suitable to each national context. Partnerships across sectors, disciplines and settings are a necessary component of healthcare, especially when it comes to integrating new interventions that may require a significant initial investment. This partnership approach is being advanced in many countries, with dialogue between industry, regulatory agencies, professional societies and patient organisations recognised as invaluable to ensure innovative approaches make their way to patients as quickly and feasibly as possible.

A recent positive example of how this can be done was the decision by NHS England to adopt a ‘liquid biopsy first’ approach for people with advanced lung and breast cancers, enabling them to access targeted treatments more rapidly. This decision was the culmination of a partnership project involving leading cancer research centres, the NHS and the developer of the technology; careful evaluation of how liquid biopsy could fit into, and modify, existing care pathways; and a comprehensive evaluation of the long-term clinical and economic impact of such a transformation. Injected with a dose of political will, this created a ‘win-win’ for patients, healthcare professionals, health systems, science and society.

Charting a way forward

We are at a unique crossroads in healthcare. On the one hand, the advances in science, data and technology offer incredible potential. At the same time, the financial and resource pressures on our health systems are undeniable and will continue to grow with an ageing population, whom we increasingly rely on for societal and economic productivity, presenting with multi-morbidities.

Change and innovation are integral to advancing healthcare, and we all need to work together to ensure they are feasibly built into our health systems. Adopting a value-based approach is key. But this cannot be synonymous with focusing solely on the costs of health investments. Instead, we must look at the social value and full outcomes afforded by these investments, shifting the narrative from immediate budgetary impact to broad macroeconomic contribution. It will be vital to understand what finance ministers need to see to justify increased spend, much of which is likely to be funded by borrowing, so must offer a strong promise of growth. In return, ministries other than health need to engage with health as an area of real opportunity, and give it a fair hearing equal to that given to other national infrastructure investments.

This shift in mindset is essential to enable our investments in health to meet the combined aim of delivering better care to those who need it, protecting the financial sustainability of our health systems, and contributing to healthier and more productive populations – making ‘health equals wealth’ a reality for all.