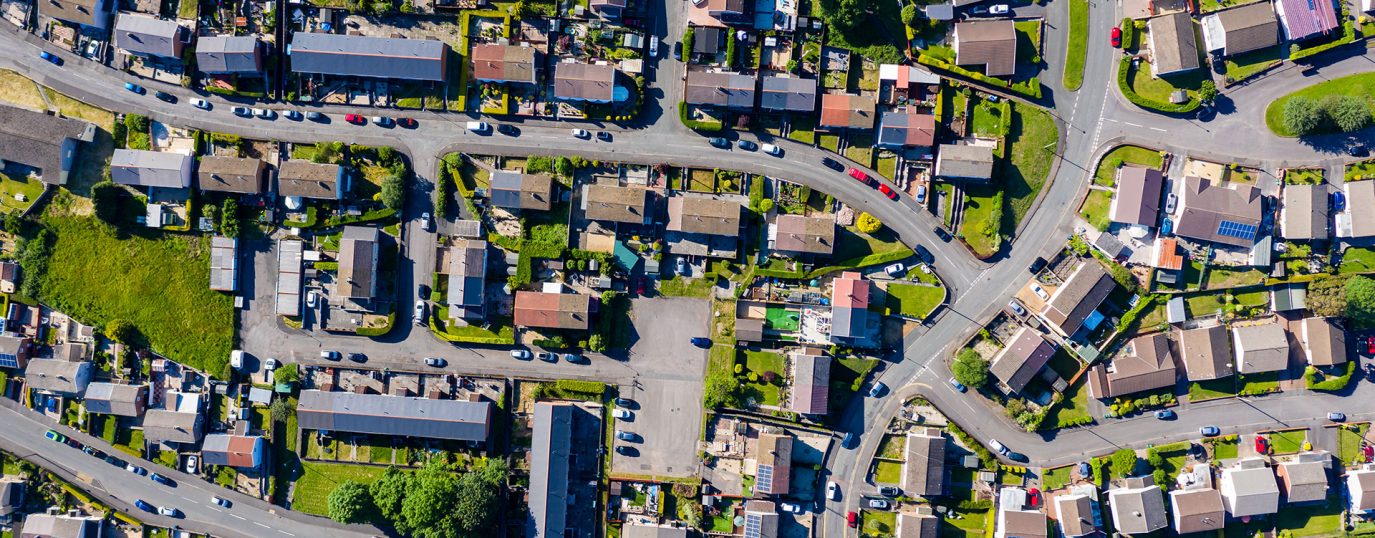

Access to housing or shelter is a fundamental human right. While the trajectory to homelessness is complex and non-linear, it is socially determined by economic, interpersonal and individual factors that are closely interlinked.

In the UK, sleeping rough is the most obvious form of homelessness, with rates doubling over the past ten years. Between March 2020 and April 2021, over 11,000 people slept rough in London – at the time, the UK government advised people to stay at home to limit the spread of COVID-19.

Less visible forms of homelessness include staying in crisis accommodation and shelters. Couch surfing – staying with relatives or friends – is an ever-growing issue in the UK. These efforts to avoid being out on the streets are often missed, constituting a hidden form of homelessness.

Housing, health and human rights

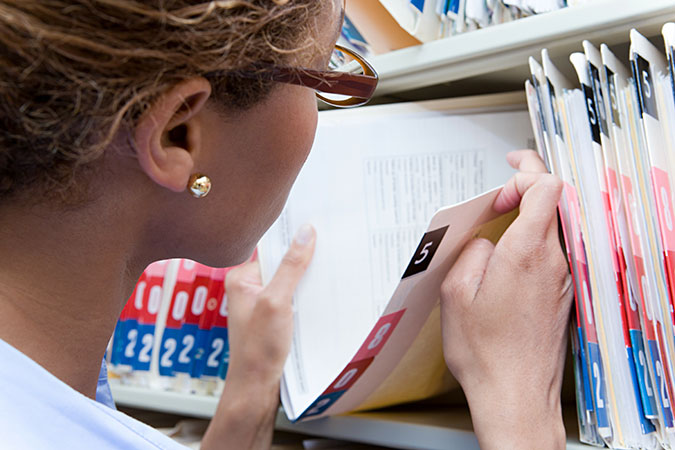

Homelessness is often exacerbated by other social determinants of health, including unemployment, poverty and domestic violence, and is often preceded by social exclusion and adverse life events that occur in childhood. However, the determinants of health that are associated with homelessness are rarely captured in hospital data, limiting our ability to provide effective healthcare for homeless people.

The right to health – through a system that provides equal opportunities and doesn’t discriminate on the grounds of age, gender, ethnicity or any other characteristic – is another fundamental human right. People who are homeless use acute services more often; they are frequent hospital presenters, with high rates of unplanned admissions and readmissions, and prolonged length of stay.

As homeless people are more likely to choose food or shelter over seeing a doctor, they may only seek medical care when a condition becomes life-threatening. More complex and expensive treatment may be needed at this stage, making the provision of care challenging. Unfortunately, late presentation is often viewed as negligence or carelessness rather than a struggle to survive, despite competing needs being fundamental barriers for people who are homeless .